Why the confusion?

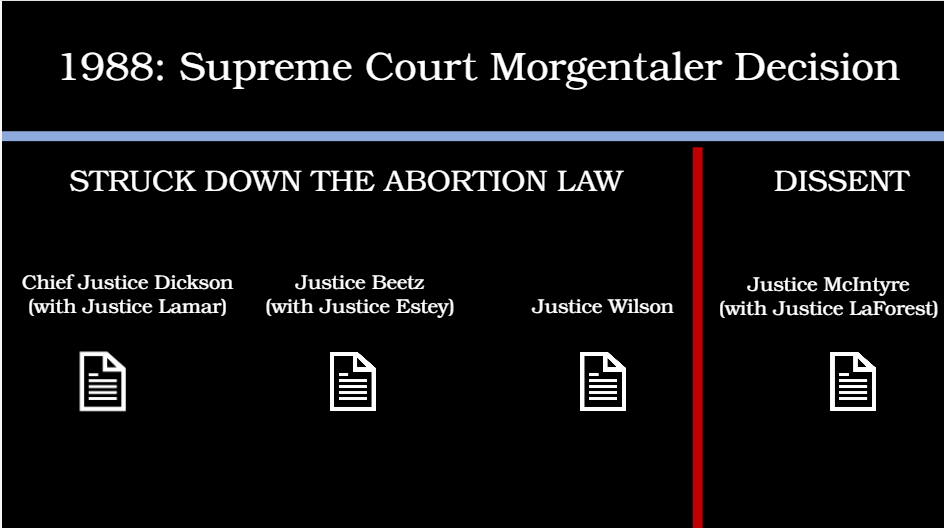

One of the reasons for the confusion is that Morgentaler is not really one decision – it’s four decisions. Every time Canada’s Supreme Court hears a case, each sitting judge has the option to write their own decision and the reasoning for it. In Morgentaler, four judges opted to do so.

Three of the decisions, endorsed by a total of five judges, struck down the existing abortion law, while one decision, endorsed by two of the judges, would have upheld the law. This means that while the result is clear – the previous abortion law was struck down as unconstitutional – the reason why is not at all clear, because five different judges arrived at the conclusion in three different ways.

This means that when we draw conclusions from the Morgentaler case regarding abortion in Canada, it must be done with qualifications and by drawing from the various reasons.

While it is difficult to get a clear sense of what Canada’s law is from this case, there are three main takeaways that everyone in the pro-life movement should know from Morgentaler.

#1: The Court did not decide the abortion question.

The Supreme Court did not demand abortion to be legal. They merely found that the former system involving hospital-run committees was arbitrary and unfair.

Chief Justice Dickson wrote in his decision: “[T]he task of this Court in this is not to solve nor seek to solve what might be called the abortion issue, but simply to measure the content of s. 251 [the law on abortion at the time] against the Charter.”

The Supreme Court justices did not decide whether abortion is or is not moral. They did not consider the humanity of the pre-born child nor (with the exception of Justice Wilson’s decision) whether women should or should not have a right to abortion. Instead, they started from the premise that abortion was legal at that time and they examined that law specifically.

In 1969, an amendment to the Criminal Code was passed by Parliament that created an exception to the general illegality of abortion. In practical terms, abortion was illegal unless the pregnant woman received a certificate from a Therapeutic Abortion Committee appointed by a hospital that continuing the pregnancy “would or would be likely to endanger her life or health.” It was this system that the Supreme Court was looking at in the Morgentaler decision. And, to put it succinctly, they found this system of approving abortions to be arbitrary and unfair because hospitals could refuse to appoint a committee, or a committee could take a long time to make the decision, meaning the abortion happened later in pregnancy and had more health implications. Therefore, the majority of judges found a breach of the Charter’s section 7 guarantee of life, liberty and the security of the person.

#2: The Court did not find a right to abortion for women.

Justice Beetz articulated this clearly, saying that, given the abortion law’s placement in the Criminal Code, it “cannot be said to create a ‘right’ [to abortion], much less a constitutional right, but it does represent an exception decreed by Parliament.” Chief Justice Dickson didn’t even consider the question, but merely focused on the specific regime chosen by Parliament.

Some of the confusion around this point is possibly due to Roe v Wade in the US which did find a right to abortion for women. Canada’s law does not have an equivalent decision. To quote current Supreme Court Justice Sheilah Martin (appointed in 2018 by Prime Minister Trudeau), “the Supreme Court did not clearly articulate a woman’s right to obtain an abortion… and left the door open for new criminal abortion legislation when it found that the state has a legitimate interest in protecting the fetus.”

The one nuance to this point comes out of Justice Bertha Wilson’s decision. Writing alone (meaning her reasons were not endorsed by the other judges), she found that women “do have a degree of personal autonomy over important decisions intimately affecting their private lives” which included in some circumstances the choice to have an abortion. But it should be noted that, in her own estimation, this was not without limits. Which leads us to our third takeaway.

#3: The Court expected Parliament to pass a new abortion law.

Justice Bertha Wilson, after finding women ought to have a “degree of personal autonomy,” limited this by saying a woman’s “reasons for having an abortion would, however, be the proper subject of inquiry at the later stages of her pregnancy when the state’s compelling interest in the protection of the foetus would justify it in prescribing conditions. The precise point in the development of the foetus at which the state’s interest in its protection becomes “compelling” I leave to the informed judgment of the legislature.”

In other words, Justice Wilson expected and endorsed a law restricting abortion at least in the later stages of pregnancy. She doesn’t dictate what that law should be, because that is not the role of the Court. It is Parliament’s role as the institution responsible for passing laws in Canada. The Court’s role is limited to examining laws in light of the Charter, as they did in Morgentaler.

Conclusion

The Morgentaler decision did strike down the previous abortion law and, due to the inaction of Parliament, Canada has had no abortion law since. But, in the Morgentaler decision, the Supreme Court was not intending to settle a question about abortion’s legal status, did not discuss what rights the pre-born child should have, did not find a right to abortion, and properly looked to Parliament to consider these vital questions and then pass appropriate legislation.

This is why we focus on Parliament, urging them to answer the call of Morgentaler, including the call from Justice Bertha Wilson to legislate with reference to their “interest in the protection of the foetus.” All these years later, Parliament needs to do what it should have done then: pass a law that begins to recognize the human rights of the pre-born child.