“Many who before regarded legislation on the subject as chimerical, will now fancy that it is only dangerous, or perhaps not more than difficult. And so in time it will come to be looked on as among the things possible, then among the things probable;–and so at last it will be ranged in the list of those few measures which the country requires as being absolutely needed. That is the way in which public opinion is made.”

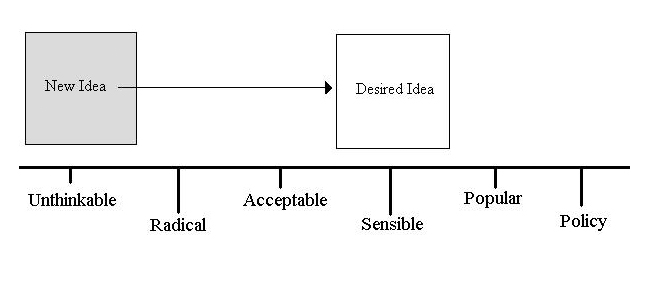

The quote above, taken from the novel Phineas Finn, encapsulates the Overton Window theory that an idea can transition from the unthinkable to even discuss, to acceptable, and eventually be transformed into public policy. In his 1868 novel, the author Anthony Trollope tackles contentious issues in British parliamentary politics such as the political viability of voter reform and the implementation of the secret ballot.

It’s nearly one and a half centuries since Anthony Trollope wrote his novel, but his expressions of what is now known as the Overton Window theory can be aptly used to describe the process of social reform in Canada today. Think for example of same-sex marriage; it used to be considered unthinkable and now it’s public policy. In fact, in 1999 the federal government passed a resolution calling on Parliament to use all necessary measures to defend traditional marriage. While this did provoke a de facto debate on the use of the “Notwithstanding Clause”, the resolution wasn’t enforced and only six short years later same-sex marriage became official public policy.

It’s nearly one and a half centuries since Anthony Trollope wrote his novel, but his expressions of what is now known as the Overton Window theory can be aptly used to describe the process of social reform in Canada today. Think for example of same-sex marriage; it used to be considered unthinkable and now it’s public policy. In fact, in 1999 the federal government passed a resolution calling on Parliament to use all necessary measures to defend traditional marriage. While this did provoke a de facto debate on the use of the “Notwithstanding Clause”, the resolution wasn’t enforced and only six short years later same-sex marriage became official public policy.

For several decades, the abortion debate has been toxic. Efforts at discussing pre-born human rights were quickly suppressed and those who prompted these discussions were labeled as extremists. Using the Overton Window axis, abortion was in the ‘unthinkable’ category. Canadians didn’t engage on the issue and much less so Canadian parliamentarians. How often haven’t we heard it said: “If you want to commit political suicide just start talking about abortion”?

While Canadian’s views on abortion have remained similar for many years (approximately 75% of us oppose third trimester abortion and the number is even higher for sex-selective abortion), our ability to converse about it was relatively immature. That said, in the last 6 months we’ve seen a marked change in our openness to debate the topic. To discuss abortion is no longer unthinkable and events over the past number of weeks have confirmed that Canada has taken a collective leap on our trip across the Overton Window axis.

In short order we’ve observed:

- Ten members of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s front benches voted in favour of Motion 312 (a motion which called for a parliamentary committee to study the Criminal Code definition of a human being);

- The introduction of Motion 408, a motion to condemn sex-selective abortions;

- Canadian women coming to the defense of Minister for Status of Women Rona Ambrose who voted in favour of Motion 312;

- Brent Rathgeber (MP for Edmonton-St. Albert) recently published a blog post openly calling for Canada’s legislative vacuum to be filled;

- Respected journalists from all sides of the political spectrum questioning this country’s lack of legal protections for children in the womb;

- And lastly, the hundreds of petitions presented in the House of Commons combined with tens of thousands of pieces of mail sent to MP’s on both sides of this issue.

Sure, there are still some who are working hard to prevent the debate from happening, and as they are increasingly made aware that they have failed, seek to polarize it with their extremist views (think of those who threw Minister Ambrose under the bus for voting in favour of Motion 312), but all signs point to the debate moving into the ‘acceptable’ range.

Which begs the question: Why is it now acceptable to debate abortion? What has changed? Well for one we need to acknowledge the efforts of Kitchener Centre Member of Parliament, Stephen Woodworth and his private members motion to look at the definition of a human being. The subsequent commentary surrounding this motion has been characterized as a “debate about having a debate” and in reality this is what transpired over the nine month period between Motion 312’s birth and death. Another reason abortion is more acceptable to discuss is the growing awareness that Canada stands alone among all other democracies as having no legal restrictions as to when a women can request or receive one. The end result is that an abortion debate is no longer viewed as unthinkable, but rather it is entirely acceptable if not a sensible one to have. Journalists may not be racing to catch up with this issue with the speed at which they go after say, Justin Trudeau, but it’s certainly receiving the attention that has been lacking for many years.

Abortion legislation may still be seen as chimerical in Canada, but all Canadians should be encouraged that debate is accepted and the level of it is rational, acceptable, and sensible. We may not be moving across the Overton Window with the same fleet footedness of same-sex activists, but those who advocate for pre-born human rights can be encouraged at the progress. By focussing on the common ground shared by the majority, public opinion is changing and a shift in policy is surely within reach.