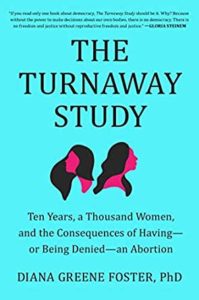

The Turnaway Study explains the findings of a unique study which follows 1,000 women who sought abortions. Gloria Steinem’s glowing review graces the cover: “If you read only one book about democracy, The Turnaway Study should be it.” Arguably she’s overhyping this book by Dr. Diana Greene Foster, but it was true that I got my hands on it as soon as I could.

For the study that forms the foundation of the book, recruiters went to abortion clinics in the United States that had a second trimester gestational limit and found women who were turned away – that is, denied abortion because they were too far along in their pregnancy – and women who received an abortion just under the gestational limit. Over the next five years, they periodically followed up with these women, asking about their physical and mental health, their aspirations and financial situation, and the well-being of their children.

For the study that forms the foundation of the book, recruiters went to abortion clinics in the United States that had a second trimester gestational limit and found women who were turned away – that is, denied abortion because they were too far along in their pregnancy – and women who received an abortion just under the gestational limit. Over the next five years, they periodically followed up with these women, asking about their physical and mental health, their aspirations and financial situation, and the well-being of their children.

The goal was to compare the outcomes of women based on whether they received or were denied an abortion. Does abortion hurt women? Is abortion just another medical procedure? Now we have 1,000 women’s perspective on this issue.

The findings of the study are fascinating and don’t lend themselves to quick conclusions. I want to take some time to unpack what the book says, so this is Part 1 in a series of six blog posts about The Turnaway Study. My hope is that by the end you’ll have a clearer picture of the lives of women who seek abortions and how the pro-life message impacts them.

Let’s start with the assumptions made

Dr. Foster begins and ends with the assumption that choice is good for women. Despite this assumption, however, she does ostensibly write for both a pro-life and a pro-choice audience. She works hard to, in her words, “put myself in the shoes of someone who was concerned about the harms of abortion.” I’m willing to take Dr. Foster at her word that she was trying to be unbiased, but the problem is she can’t be neutral, especially when it comes to the heart of the pro-life position: the humanity of pre-born children.

In the introduction, Dr. Foster does acknowledge that this study “will never resolve the moral question of when a fetus becomes a person,” but she gives shockingly little time to even considering the impact of this question on women. The closest she comes to actually dealing with the question of the humanity of the pre-born comes from a story of one of the women in the study who muses, “in the ethics class, we were talking about when is something considered alive. I’ve always thought it was when it has a personality of some sort.” But this question is noticeably lacking from the rest of the book, leaving the reader missing a crucial part of the equation.

When Dr. Foster discusses the children born to women who were turned away for abortion, she says, apparently without irony, that “women’s lives…are not the only lives affected by the ability to access abortion care.” We agree. Pre-born children’s lives are intimately and fatally affected by abortion. But she neglects this entirely, spending the chapter only considering the outcomes of children that made it to birth.

She concludes that, “enabling women to have abortions when they want them increases the chance that they will become pregnant later when they are ready and prepared to parent.” She assumes that future children are interchangeable with the present child, ignoring the reality that each life is unique and intrinsically valuable. She also states that many women “choose abortion with the needs of children in mind,” but we must point out that clearly it is not the needs of her pre-born child that are being considered.

How this plays out in women’s lives

These individual, unique lives lost to abortion are still present in the women’s stories that Dr. Foster tells throughout the book. One example is that of Ariela (all names are pseudonyms), who at 19 chose to abort twins. Ariela’s reasons included wanting to finish school and establish a career, and the book includes her jarring summary that “I gave up two lives for myself.” We are not comforted when she elaborates: “Like, I gave them up so I could have a better job, which I do, and so I could go to school, which I’m halfway there, and to have a better life, which I think I’m doing okay.” Her plans to go to law school and seemingly have a “successful” life ring hollow to those who mourn the lives that were lost.

This oversight by Dr. Foster is revealing of the heart of the abortion debate. As Greg Koukl succinctly put it, “If the pre-born is not a human being, no justification for abortion is necessary. However, if the pre-born is a human being, no justification for abortion is adequate.” If Ariela’s twins are not human beings, then we have no reason to question her decision to prioritize her career. But since we know that life begins at fertilization when a unique, distinct human being comes into existence, no accomplishment will come close to compensating for the tragedy of two lives cut short.

What we are able to resonate with are stories like Jenny’s, who was denied an abortion, had her child, and “started crying at the thought of her then-six-year old no longer being in her life. ‘She is just everything to me.’”

Dr. Foster undoubtedly is aware of the argument for the humanity of pre-born children, but always portrays it as an opinion. She deliberately suggests at times that a woman or those around her could “consider” the pre-born child a baby. But she never confronts the question: what if it isn’t just an opinion, but a woman is actually making a choice to end another human being’s life?

If you are going to ask the question of how abortion impacts women, that must include considering how the loss of her child impacts her. But Dr. Foster is not neutral on this point, deliberately sidelining the central tenet of the pro-life position.

The pro-life movement has thought about the women

While she largely ignores the very truth that motivates the pro-life movement, I generally am willing to take Dr. Foster at face value when it comes to her attempt to be unbiased. However, I must take issue with the way she characterizes the pro-life movement as not even thinking about the women.

She pronounces this judgment by telling a story of a pro-life American politician responding to a journalist’s question of, “’What do you think makes a woman want to have an abortion?” Obviously caught off guard, the politician stammers a bit before offering, “It’s a question I’ve never even thought about.” From that single instance, Dr. Foster concludes that, “In the decades-long battle over abortion rights, this one moment completely captures the disconnect between the politics of restricting abortion and the lived experiences of women who want one.”

In one fell swoop she ignores the many in the pro-life movement, including those of us in the political realm, who have spent countless hours seeking to understand women’s lived experience. People like Frederica Mathewes-Green who detailed the lived experiences of women in her book Real Choices. Or the brave post-abortive women who use their stories to highlight the reality of abortion. Or the countless people across both the United States and Canada that keep pregnancy resource centres going. These centres are devoted to understanding why women are seeking an abortion while promoting options that are best for her and her child.

We have thought of the women. And we have thought of the pre-born child. The reality is that the choice for abortion is not about one person, but two. Some in the pro-abortion movement, like Dr. Foster, will try to claim it is only about the women. Others might view it as woman versus child. But the pro-life movement has the radical belief that we can be for both woman and child.

We’ll delve into that more in Part 2, when we consider what is actually best for women.